Interview with Maria Dimou

With a spring mood, the artist Georgia Bliatsou welcomed us in the “embrace” of her workshop and introduced us to the stories hidden in her works, the exquisite portraits, the colorful natural landscapes, the inventive crafts and constructions that she creates with so much passion.

In a space full of life and aromas of various flowers of the time, the artist opens the box of the past and reaches the present. She reveals to us a very dear piece of hers, which she is currently working on, which is none other than nature and magic, giving now a taste of antiquity. Her motto: “Creation is communication”.

Georgia Bliatsou studied at the Athens School of Fine Arts and later took over the teaching baton with a fifteen-year contribution to secondary education as a teacher in the field of art.

She has participated in a total of 25 group exhibitions, both abroad and in Greece, among her most important distinctions are the one in the Bulgarian Biennale in ’89 and others in foreign countries, such as Germany and Poland. Her works can be found at the Orthodox Academy of Crete, the Vorres Museum, the Diachronic Museum of Larissa, the International Hippocratic Foundation in Kos, Rowaq Al-Balqa Foundation, Amman, Jordan, in a private collection at FIladelphia USA, Credit Lyonnais and other private collections worldwide.

Her themes include portraits and natural landscapes with Mother Nature as her main source of inspiration. For her objects, she uses mainly wood, metal and plexiglass. In recent years, she has been faithfully engaged in the study of the historical past and its magical connection with today, because according to her, tomorrow does not exist without yesterday. He is also involved in book illustration.

It operates in Athens and Kea (Tzia), two particularly important places for her. In her paintings so far, she has dealt with shadows, flowers, animals, scenes from the Revolution, the sea, life, absence and their combination, as well as loneliness with a nostalgic, yet optimistic breath.

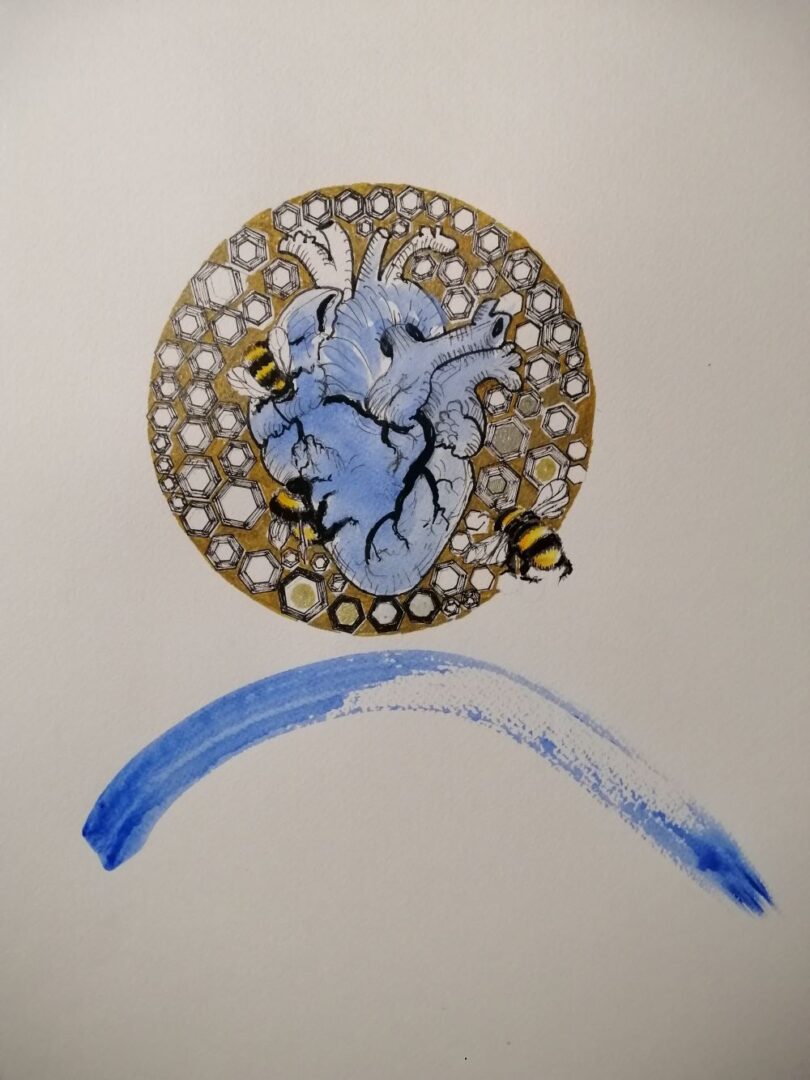

There is a very nice Irish proverb that says: “When someone leaves this life, if you have not told him things you wanted or dared to tell him, tell the bees. They will pass it on to him.”

Her artistic career begins with an innermost look at the community of Kea. A thorough portrait of each of the people of her beloved island, translated into paintings and interviews in the book and the corresponding exhibition: “Inventories of memory-Testimonies from Tzia”, located at the National Library of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation.

In a well-travelled and rich in experiences journey of cultures, customs and idyllic locations -which inspired the majority of her works- Georgia Bliatsou of today, explores the “bee” and its fascinating history from myths to its importance and diverse aspects in a series of works entitled, “Honey & Milk”.

– What were your first steps in the artistic field?

– I decided to do a job related to identity and because in Athens it is very difficult to find a group of people who have common characteristics, I started from Tzia.

I have a house in Tzia and there I would say that it is my second place, it is not my birthday but it is a choice that I loved very much. I started with the oldest, started interviewing them and worked my way up to the younger ones. I covered all professions: from street sweeper to university professor and shipowner. So we have a society that is the depiction of Greece, a miniature of Greece. And what I finally realized is that people learned about Tzia – which was an unknown island – much later, even though it is very close to Athens.

People went through a lot of poverty, occupation, they got money from very few professions and it was essentially an exchange society. They were proud people. They toiled, they worked, they loved their land and they fought in it, under wild conditions. Their land is not as fertile as Thessaly is or as it is on Macedonia. They succeeded. So with the interviews there was a record of professions, some of which were lost. I learned so much from them, really.

When I started researching I felt we were stigmatized as a race and after that I felt proud. Because history is not only written by historians, it is written by each person, each person has his own personal story. And that was very important because it was also a psychogram. Women of the same age, in the same place, raised in the same place, one with a positive thought towards life, while the other with a negative thought, you see what each one got, because what matters is the attitude we hold towards our lives. This was also an exhibition, both in Athens and in Tzia. The recordings of the people in Tzia were two hundred, that is, 200 portraits and 60 interviews.

Because as the African proverb goes: “If you don’t know where to go, see where you come from.”

– What was your next “stop” and what did you want to deal with in it?

– After finishing this, which has an ethnographic and folklore character, what concerned me is how the creator affects his place, creative thinking. Because in our lives we only have political thinking. Which political thought ultimately limits the place, limits horizons. Because I believe that the role of art is to open up paths, I wanted to see how creative thinking affects society. I started from my birthplace, Larissa, which has many artists. Visual artists, remarkable musicians, writers, poets and archaeologists. Because as the African proverb goes: “If you don’t know where to go, see where you come from.” This is crucial, because I have always been interested in the story behind everything I do.

In Larissa there were 50 interviews, where for each one the questions were: “What is art for you?”, “How do you see your life?” or “Would you like your work to have a wider scope than the city limits?”. We have musicians who are famous abroad, like Papathanasiou, female conductors with careers in Germany and Austria. It’s a charismatic world. This exhibition took place at the Katsigras Gallery. It was supposed to last a month and eventually lasted for two months because the place was open to us for schools we painted with. We were talking about what a portrait is, how to set up an exhibition, how to make a book, we did a workshop… It was a very great contact with the audience and it was very interesting!

– Taking even a brief look at your work, one can easily notice that you have a special relationship with nature. Where do you get your inspiration from?

– Due to my origins, the sections of my work have great contact with nature. Thessalian plain, landscapes, flowers. Then, due to the existence of Hippocrates, who died in Larissa, I made a section with his four elements: water, fire, air and earth. And this represented birds, flowers, seas, ships and there were some exhibitions in the province, in Kos, in Larissa.

Nature concerns me, my work is essentially nature and man, the environment and the way we move. I believe that life is art when you live it, and everyday life too. That is why I deal with the visual object because it is not an object that will simply enter a museum, but is in our daily lives. All arts are a marriage. I feel that man is very balanced when he enters this world of art.

– You have devoted a large partof your career to secondary education.

– I taught for fifteen years in secondary education and there you could see how far all the lessons were from our lives. We feel that they are alien to us and maybe it is the way they are taught that is wrong. When you start adding things from everyday life to them, sooner or later we will understand that one has something to do with the other. That’s why our children are a little uninvolved, even very much. Of course, they listen to what is happening in society. A society that does not love art, does not know its history and does not love its place. And it shows. We say that we are descended from our forefathers and they are so distant relatives. It’s like they’re completely different. Whereas through study, through history you acquire this link. That is what we must achieve.

– So, according to your own personal experience in the field of Secondary Education, what is your comment on how to learn art in schools?

– Art is not something foreign from us, it is us. If a good job is done starting in elementary school, children are so easy to understand. It is simply the wrong tactic. And this also leads to the question of what kind of society do we want to have, when we have made changes in education by removing subjects such as art, what will the next generations be like? It’s sad because our children are so talented. Based on my experience, and indeed at the beginning when there were many exhibitions with children from the European Union, I could see that our own children were indeed comparatively much superior. They have an independent spirit and from a young age man has not learned to follow certain things, he has his own course.

We see that through the images presented, however, they lose their imagination. It seems that they do not trust their own way and abilities and want another, ready. Especially now, after the coronavirus period when children from a young age are in front of a screen, they have a ready-made image. Talking from kindergartens to primary school, this was a big shock for the children. They no longer dare to have images of their own. We make copyists, not creators. Not everyone will become an artist, but what matters is that the child trusts himself and can expand the boundaries of his imagination. After all, what we creators do is go further and further down, we take out our fence little by little until we completely tear down the fences. This is the ideal situation.

– What did you gain from your teaching years?

– My experience in secondary education was a good experience, but at the same time it deprived me of being able to have free time to do exhibitions outside Athens. And that was why I resigned. And to be honest, when I entered schools I had the same feeling I had when I was a student, that schools were prisons. So, in all the schools I went through, I tried to make a “library”, for the lesson to be creative, I demanded that we have our own classroom, where the children worked with music, freely. And in the end when we were doing exhibitions, they didn’t think these works were theirs.

I have crossed the whole basin in different areas and I still feel this warmth from my students. Today, after so many years, they are texting me. That is a very good thing. Some became jewelry designers, engaged in animation, some other children fled to England. It’s good to feel like you’ve given something. Of course, I always ran with my own projectors and equipment as the schools were not so organized. You open doors to them through it.

That was the good side of education (being remembered by my students). The bad thing is that schools should rely more on the arts, teach more language, more history, better Ancient Greek and Mathematics, but through art. We are too deprived of the way to teach something. While, getting children to school is considered to be number one for the Greek family.

– Who or who would you say were the ones who pushed you to start this artistic path -among others- of yours? Who do you consider your teachers?

– Starting of course from the classics, about which what to say… Rembrandt, Van Gogh, his relationship with Gauguin… They were legends in the field of art but apart from legends it was also their way of life, they claimed their touch, their color, they did studies. Then, Picasso, Goya. I’ve seen amazing exhibitions by Goya, a huge anti-war voice. Then I admire the Russian school, with great artists and younger ones. There are also many younger painters who are sensational.

At school in Larissa we didn’t have the art class, we had a handicraft lesson. Because I was involved in hands, cutting, sewing, it was good for me. I began not to be afraid to deal with my hands. He was an architect, a very friend, who had finished the Bauhaus and Vasilis Nikolaidis was coming, and John Michas was coming with him. The artist who brought the abstraction to Greece. He was an occasion. I was too young at the time and I was painting on my block. Of course, from a very young age my desire was to travel the world and deal with art.

I didn’t know what this art would be, it was elusive. But I felt like that’s where I was committed. And finally I did my travels and I have traveled a lot. And this is a very great experience, because you see other cultures, other customs and traditions. I liked very much African culture, which is completely different from Europe, just as Asia has its own values again, or the East. So I have knowledge of these cultures. This is a good suitcase in your life. Then I went from Vakalo where I had Dimitreas, who of course was very theoretical, but from his theory I got some things. They were question marks to open some doors to reading and research. Then I went to Fine Arts. There I had teachers Kokkinidis, Mitaras.

– You have traveled a lot in your life so far and this is reflected, one would say, in your touch. What was your “study” abroad?

– In California, Richard Smith, a very good painter, who painted a lot of outdoors, portraits. And there, he and a number of many other good painters – some specializing in landscape, another in watercolor, in oils – teach. This lasted a week. This kind of teaching there was a tremendous experience for me. I compared it to five years in Fine Arts and it made a huge difference because people teach differently. First, they love what they do, not that ours don’t, but I would say they didn’t have the method.

At school you felt you had to know everything. Which if you knew why be in school. Only one teacher was involved in the minutes, who was indeed a teacher, and that was Tetsis. The rest were more theoretical. I, of course, succeeded Kokkinidis at a time when he had many problems and that is why his participation in teaching was small. But the fact is that these seminars in America were particularly important.

And of course they were done with all the professionalism. They show you materials, everything there is from easels and equipment. We didn’t have that in Fine Arts. The “kitchen” of painting is the materials. We go directly to the most modern and forget the simplest ones that are the most basic for your first steps. We start in reverse. And we start with all things in our lives in reverse. We are coming to dead ends, when you can just pave a way for us all to go. We, however, are looking to climb.

You are a woman who, as you said, has in your possession a full suitcase of experiences, especially from abroad. In the meantime, however, you contributed with your own contribution to secondary education, painting, sculpture, handicrafts, but at the same time you were a mother.

– In life there needs to be a balance. I have taken many different professional steps but I have also been a mother, not just an artist who is in a studio closed and working. I also wanted to go around the world, take breaks and travel. And that’s part of my life, my ego. There are so many artists who are dedicated to their work and work in a room. To their credit. As I get older I understand that this takes work and I feel guilty if one day passes and I can’t work. But I need everything else, I need to take other, new images. So I try to balance between gaps and work.

In the coronavirus I felt very happy to have all this time to myself. Suddenly everything stopped, so all that time empty, which before was full of things going on out there and I didn’t want to waste them. But it is part of precious time, and the concept of time is paramount in our work. You take time away from your job and get something else in return, but you can’t do it all the time. So those two years were precious. I turned night into day and enjoyed my work. I had time to clean my workshop, to see my materials. It was not easy to do this in everyday life, as various obligations are running.

I’m a woman who was told at first, “You’re going to get married, you’re going to have kids, and then you’re going to stop doing this at some point.” We don’t have support, it’s a One-woman Show. You have to do both the manager and the public relations, do everything. It’s not easy. But if you love, you will persevere and you will achieve something. We don’t expect things to be ideal because we’ve learned that we can’t have ideal conditions, so we adapt and fight for it.

– We are going through a global crisis both economic and cultural. What is the relationship of today’s man with the arts and what specifically with painting?

– It is important to express yourself, to be able to convey this. For me, music is what goes straight to the heart. You don’t need to know her language. You listen to African music, you listen to jazz, whatever you hear. Music can make you cry. With painting, however, this is more difficult. In painting you have to have some knowledge. The opera combines everything, the music, the image, the costumes, the sets. It is the culmination, so to speak, of the arts. But we had no such tradition, so we are less initiated. I wish painting could reach this. There are many trends in painting and it is more difficult for the viewer to get what the creator offers him, because he does not have the necessary knowledge. He can easily reject it for this reason. It takes an education to be able to climb these rungs of knowledge.

– Where are you now and what are the topics you are currently working on?

– Now I study honey and milk, which are the foods of the Gods. Honey took me to bees, as I was currently staying in Tzia where it has many hives but also because the bee is an insect that marks the course of humanity, because if the bee disappears and we will not have more than 4-5 years of life, the destruction of the planet and all those phobias that surround us.

But the bee is also the model of a society like those of insects and animals, which is indeed admirable with many references in ancient Greek literature – the priestesses of Demeter were called Melisses – and symbolism. There is a very nice Irish proverb that says: “When someone leaves this life, if you have not told him things you wanted or dared to tell him, tell the bees. They will pass it on to him.” It has a psychoanalytic meaning, like say it somewhere and don’t keep it inside you, but the bee from antiquity is considered to have been the psychopomp. This tender insect which carries messages. Then, of course, we move on to milk, which Zeus was essentially fed with honey and milk.

As for the milk chapter, it is a record of all the animals that give milk, sheep, goat, the donkey, the buffalo. In ancient times, because most of the time the legs of buffaloes were in the water, they were said to have blue legs. Studying you see extraordinary things. You see images, myths that touch reality. In fact, this is what I am currently studying. And of course, what is surprising is that both milk and animal skin are thrown away today. In Tzia, milk is not given to industries because it is not economically profitable. Either they make it cheese or they throw it away, including wool, whereas they relied on wool for centuries and we had all households relying on hair weaving.

Now within this research, I see that in England they began to make wool fertilizer for crops. Which wool of course, because it is organic, decomposes and gives the earth all these elements. What connects me to antiquity, going from Thessaly to Tzia, so did Aristaeus. It is God who in ancient times taught systematic animal husbandry and beekeeping. Tzia has many parts of it that have melissaki. They had hives and honey flowed. At Akrotiri in Tamelos they collected honey from wild bees. Its story matters to every issue, I’m not just a tourist in one place.

– Hence your systematic research on its history…

– I am interested in this place. It is an exchange relationship, I give him and he gives me. What we take and what we leave. And my big question is: What are we going to leave as a generation? What will we leave from an architectural footprint in our country? I don’t know if we are protecting the planet. There are balances, regardless of whether we think they are not in our economic interest, now that the economic factor is an obstacle to everything anyway.

– What is happening with the art market today and where are we heading as a society?

– A few years ago, before the crisis, things were much better. There was an average audience that was buying, and that was limited and increasingly restricted. It’s not that there’s no audience, but it’s limited anymore. In America and California in particular, where I went through various galleries, there were different “rules”, that is, there the galleries consist of five or six artists exhibiting their works, whereas here things are more confusing.

Today we listen to what is happening around us because we have the ability to get the vibes of the era, which has many question marks and negatives. The thing is, if you’re not an optimistic person, you can fall into depression. Fortunately, creation gets you out of it. But things are not very positive. I would say that we are lucky to experience them, because all historical eras have had their descents. Through it we come out stronger.

But there is a wait for the moment at a very fast pace. We are spectators of things that have happened that we still haven’t understood, things that leave marks. I think these two years of quarantine were a good time to spend time with ourselves, but at the same time it was a deeply traumatic experience. We were subjected to compulsory confinement, but above all you saw your fellow man as a source of infection, as an enemy. All of this is traumatic.